When you're the executive editor's only daughter you can get away with just about anything. Claudia was the youngest reporter to have command of the city desk at Il Piccolo. She had finished journalism school six months early and had bypassed, thanks to her father's ironclad hold on the payroll, any newspaper's usual route through classifieds and local zoo birth stories. No one dared to question the boss's decision or to ask about her talent. Claudia had demonstrated her writing ability at the University of Firenze, having gone from copy girl to senior editor to executive editor in less time than all of the previous prodigies. In her junior year she had uncovered a scandal involving the night janitors, three frat houses, the zookeeper and a bevy of local hookers and gamblers. Her written account had gone from page one of the weekly university newspaper to the editorial page of Il Piccolo overnight. Her professors emailed her literary creations around the globe as proof of their amazing ability to teach. None gave credit to her genetics and only one made mention of her familial influences; he was placed on administrative probation.

Claudia only wanted the best for herself, front page, first column, bold type, italics and underlined. When the romance novelists wrote about the spoiled only child with a face which turned all heads on the Via Roma, they had her in mind. Her father bought her the newest, fastest red Ferrari; she made him replace it with a blue one to match her eyes. He gave her a fully furnished townhouse with a wonderful view of the morning sun coming up over the distant mountains; she gave it back and moved into a barren penthouse in the center of town with a view of the setting sun played out over the gleaming neon of the uptown nightlife. In addition, she made him fill it with gleaming chrome and black leather furniture from only the finest craftsmen in Milan and Sorrento. He put her behind the city desk of the largest and most revered daily newspaper in all of Italy; she stayed there.

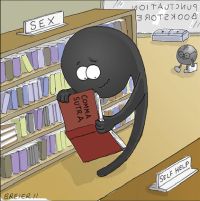

As talented as she was spoiled, Claudia had a love affair with a single keystroke and had no desire or reason to accept criticism for this solitary flaw. Claudia was in love with the comma. Whatever she composed, whether it was news of an overturned commuter bus or the scores of a weekend soccer match, the text would be loaded, overloaded, and occasionally capsized with commas. She placed them in lists, inserted them in thoughts and squeezed them into places a comma had no right to occupy. The senior editors at Il Piccolo went mad with strikeouts and corrections. How would the sophisticated readers of their daily newspaper, calmly slurping their steaming hot morning espresso, react to a continuous stumble across pages strewn with grammatical faux pax? This was not some supermarket tabloid with frayed edges from impatient shoppers; this was Il Piccolo the voce d'Italia they were printing.

All of this held as much credence for Claudia as the weekly lottery. Her love for the elegant tail of the comma in Times Roman or the sophisticated top hat comma from Playbill far outpaced her sense of grammatical correctness. How could you not like the happy face of a comma printed in Bodoni Bold or the plump little fellow produced by Goudy Stout? She would compose text in minutes and spend hours testing dozens of typefaces to find the appropriate comma to fit her desires. Occasionally she would forget to reset the typeface and the first few letters following the comma would bear an odd typeface before slipping back into Times Roman to complete the thought.

The rest of the punctuation keys were superfluous to the young editor. What could be said about a full stop? It was nothing more than a dot on the page, a lone island in an ocean of floating letters. It gave finality to the sentence. "Stop here" it said and nothing more. It abbreviated and decimalized and while it held a thought from becoming a runaway train, it was, nonetheless, only a single point in the galaxy of prose; too final and controlling for Claudia. The question mark asked and was not always answered. It left many things unsaid and often led to more questions than answers causing a thought to crumble to nothing but confusion and disarray. Quotes were necessary evils unless the writer was bold enough to lay claim to a snippet of dialog which should have been attributed to someone wiser. But they too came with an air of befuddlement. Should they be single or should they be double? What if you needed to quote within a quote? The single quote served a purpose for the lazy author who smashed together words to make contracted thoughts the average taxi driver found easy to read. But their plebian structure offended the barristers and professors who would never stoop to such a low level of conversation; contraction, indeed! For Claudia, the quotes brought far too much confusion to the table; she put everything in her words and eliminated them from her text.

Braces and brackets along with their neighbors the infamous slash family, both forward and back, were the domain of the software designers. Why else would they have such awkward locations on the standard keyboard? To Claudia a hyphen displayed a much more substantial upbringing than a half drunken line. Colons, both full and semi, were for technical writers and list builders. The colon reminded her of an apartment house populated with full stops. Its half brother below it was simply a comma who could no longer deal with singularity. It was a pause which was unsure of its social status, something she would not tolerate.

The ampersand was the illicit love affair with an 'S' and one of the slash brothers. A vulgar symbol which was best suited to join two partners in an overpriced bistro or a well traveled circus. It was another tool for the poorly motivated writer and not a keystroke which fell from her fingers. And what about the tilde, sequestered far and away from the other useful keys, what was its use besides internet addresses? Had anyone ever placed it carefully in the midst of some dramatic scene or eloquent description? It was always the cleanest key on the keyboard. The other odd and rarely used marks of punctuation residing on Claudia's keyboard had meaning to some but no place in her litany; the comma was supreme.

Claudia's adoration for the comma manifested itself in scads of unforeseen and usually unnecessary pauses in the news stories flowing from the city desk. She used commas like Krazy glue to build long winded sentences giving an Olympic miler shortness of breath. Once the adjectives and adverbs started coursing from her fingers there was nothing but muscular fatigue between her and a seven column description of a soon to be constructed outdoor loo at the art museum in Trieste. The death of a prominent member of the already overstuffed clergy evoked a hailstorm of commas as Claudia set about to canonize the suddenly departed priest. "He was gracious, loving, spiritual, sentimental, learned, wise beyond his years, understanding, caring, loving (again just for good measure) and now sadly taken from us, all too soon."

The senior copy editors would pull what was left of their hair and gnash their dentures reading these over-blooming odes to the thesaurus, but they had no practical recourse, she was the boss's daughter and could do no wrong in his mind. Several of the balding editors, counting the months to their retirement, found themselves on the dole with just a single strike of their red pen on a page of Claudia's copy. One editor, with a wall covered in awards, degrees, and famous photographs, resigned in a fit of anger when told he had best hold his comments lest he spend the balance of his career writing real estate fiction for the Sunday edition. The junior copy staff gathered daily at water coolers throughout the cavernous newsroom to chuckle and gawk at the runaway reporting Claudia produced.

She left no twig unbent as she marched her readers through the trail of a murderer's spree. She deduced it critical to tell his every step and to cement it together in a verbal map of his escapade. "The killer spent time in Padua, Verona, Milan, Como, Asti, Reggio, Rimini, Ancona, Fermo, Foligno, Spoleto, Ortona, and Bracciano before his capture in Rome this sunny, uneventful, somewhat humid, lower than average temperature, close to the weekend day." Junior pressmen at Il Piccolo's high speed printing plant would smash the brake pedal bringing the presses to a shuddering halt to find someone, anyone, who could confirm this was what they wanted to appear on page one of the nation's most respectable daily. The answer was always the same, "The boss's daughter wrote the article. Do you think he hasn't read it? He's not going to chase her into a waitress' apron. Do you value your career at this newspaper?" They slammed the presses back in gear.

Claudia took an ethereal pride each time her finger stroked the comma key. She was controlling time, putting little pauses in the reader's personal time continuum with each insertion. The pleasure she inhaled as the tiny curlicue appeared on the screen gave birth to a sigh you could hear three offices away. Everyone knew when Claudia was pleased with her work. "She turned, slowly, just as his bloody, arm, came, quickly, and without warning, none that she heard, at least, in one long, and prolonged, plunge through, without stopping, her window."

With the exception of the space bar, who was tapped more often than anything else on the keyboard, the comma was getting far more than his share of the keystrokes. And he was not as pleased as Claudia would have desired. Sometimes she would slam him with a furious tooth-yanking pain as she reached the climax of a phrase. Recently she had put as many as eight commas together creating a whole new format for the three dot ellipsis which was, in her mangled book of grammar, a row of tombstones in a story. The comma key was already exhibiting arthritis of the lower spring and at such a young age! At this rate of decline the entire keyboard was doomed.

There was only one sensible course of action - the comma key began to stick. Claudia tapped it with doorbell strength and watched the cursor hold its corner on the screen blinking in anticipation. She pushed the comma key and watched her fingernail change color but the key refused to budge. When Claudia took her three hundred Euro Mont Blanc pen and plunged it ramming speed into the white plastic cap the comma relented; we all have our breaking points. Claudia was not done. She tapped the comma several times but only got partial results. Why was her comma key reacting this way? What had she done to cause such distemper? Perhaps another keyboard was the solution and so she borrowed one from the neighboring office and connected it in place of hers. But the problem remained. The original keyboard, in constant contact with the entire network, had, in less time than it took Claudia to think about it, electronically passed on a message, and every keyboard in Il Piccolo's vast computer array clicked back and acknowledged they were ready to help.

Claudia telephoned the newspaper's computer support office and a smiling Fabio wannabe with rolled up sleeves and too many gold chains, for someone who worked with electronics all day appeared several minutes later. He tried the keyboard and found it to be in proper working order. He tested a brand new keyboard fresh from its cardboard shipping container and it worked as well. Claudia shoved him aside and tapped the comma key expecting an electrical shock but only got her favorite keystroke. Fabio returned to his office.

Unfortunately as soon as he was gone the comma stopped cooperating; Claudia's rage became a ballistic tantrum befitting a six year old who is just not going to get a gelato before dinner. She picked up the keyboard and smashed it on the dark walnut desk. The comma stayed silent. She switched keyboards and tried again with the same result, no commas. Fabio returned, one additional button open on his shirt - after all she was the boss's daughter - and made the commas dance across the screen. Claudia did the same as he watched and then left, shaking his head in disgust; the boss's daughter had no intention of spending the weekend with him.

Again she squashed the comma key and received nothing for her efforts except a sore finger and a split nail. She smashed the keyboard with a dictionary and pounded on the keys with a heavy duty Swingline stapler, fully loaded. Claudia's face filled with tears with the ugly realization commas were never coming from her fingers again. With a screech piercing the air louder than a hawk with an arrow through its wing, she beat the keyboard senseless with the heavy leather bound dictionary. Pieces of plastic flew up to cut her face, springs popped and rolled around the desk top like errant peanuts popped from their shell. She was as close to the jagged edge of hysteria as you should venture without a parachute. Her chest heaved and fell as it became hard to pull fresh air into her lungs between the rinse cycles of her tears. Claudia screamed and threw a trash can through the window; copyboys ran for the door. No one would come near her. No one wanted to see the boss's daughter like this. They would much rather face down rabid dogs with staple removers.

Claudia collapsed into her chair sobbing and shaking, the pit of her stomach turning icebox cold. She kept her back to the computer screen hoping it would go away. It took several long minutes to stop the chatters and the teardrops but she finally gathered the substance to turn and stare at the screen, horribly afraid to see the results of her tantrum. The words formed letter by letter on the silent screen, a blink of an eyelid apart, "We can help you, Claudia."

She missed a breath and skipped several heartbeats before she could read the words. Pride took the lead over fear and her first thought was, "Asshole. Probably that Fabio moron playing games over the network, he'll be driving a taxi tomorrow with his gold chains sitting in a pawnbroker's display case." Claudia grabbed the thin blue network cable and tore its arm out of its socket, a bloodless, yet violent death. It took a moment for her to remember this was a word processing program not a conversation tool. No one in the office could be typing on her screen. Fear regained the lead and the color faded from her complexion. She was over the cliff and headed for the rocks below. With what might very well be her last intelligible thought she asked, "How?" She brought the thought to life by hitting the four appropriate keys on what remained of the keyboard. The response was a single word, played out in Times Roman one letter at a time, in bold, italic, and underlined, "LEAVE".

The rest of Ricky's website.

The rest of Ricky's website.

The rest of Ricky's website.

The rest of Ricky's website.